The book of Esther is one of the books of the Bible that is truly a Biblical enigma. It’s the only book of the Bible that doesn’t mention Yahweh by name. It’s a Biblical drama in which a woman is the main hero and a man (Mordecai) is her facilitator and where these two Jewish heroes are known by their idolatrous pagan names. Finally, it is a story where the Jewish heroine, out of love for her people, is willing to outcast herself by marrying a pagan gentile king, that sacrifice then is used as the means of by which Yahweh preserved His people, and finally in a wonderful twist of destiny ends up bringing eternal honor not shame to Esther as a gentile queen of Persia.

What a thrilling, inspiring, amazing story, don’t you think? As wonderful as Esther’s and Mordecai’s story seems, there is much more to it. You see, as I’ll explain in the coming pages, once we understand the chronological context of Esther and her Persian king, the story of Esther takes on profoundly greater significance to the story of the Jewish people and Yahweh’s redemptive plan for mankind. Not only did Esther save her people from the evil machinations of Haman, but it was her Persian king who was the agent whom Yahweh used to ensure the completion of the 2nd temple, reestablish its sacrificial service, rebuild Jerusalem’s fortifications, and possibly the most important of all, decreed that Ezra, the priest and scribe, reestablished Torah observance in Jerusalem and Judea.

Consider that for a moment. Without the efforts of Esther and her Persian king the social, political, and prophetic conditions necessary for the Messiah Yeshua to come would not have been in place. Without the efforts of Esther and her king, there would have been no temple, no priesthood, no sacrificial service, and no Torah observance – all of which were prerequisites for the coming of the Messiah. Think I’m exaggerating slightly? Well, if you let me, I’ll show you just how indispensable the story of Esther is to Yahweh’s redemptive plan for mankind.

If you’ve been a regular reader of this blog then you know that the theme or premise of this blog and its articles is that all the Bible and each of its 66 books contain important events and chronological details by which Yahweh reveals His redemptive plan for mankind through Yeshua (Jesus). The Bible tells us that this redemptive plan is laid out according to a cosmic timeline preordained by our Creator. Because this redemptive plan is revealed through the Biblical ages, to fully appreciate its beauty and majesty, we must understand chronological context from which it springs.

The story of Esther and her king magnificently illustrates how important context and chronology is to Yahweh’s redemptive plan for mankind. So let’s do a little digging to see some of the treasures Yahweh has hidden in the chronological context of Esther for us to find.

Who is Mordecai?

To start with today, let’s fill in some of the chronological context of Esther by looking at what the Bible tells us about Mordecai. We start with Mordecai because the Bible synchronizes Mordecai with the Babylonian captivity of Jechoniah which we can date with a reasonable degree of certainty.

First of all, the name Mordecai (Babylonian Marduka) is derived from the name of the Sumerian and Babylonian god Marduk. Most Bible dictionaries say Mordecai’s name means “worshipper of Mars”. But as Gerard Gertoux1 notes Mordecai can also be understood as “ ‘the Mardukite (mardukaya)’ in the sense of the ‘the Babylonian’”.

Mordecai (Marduka) is a relatively rare name in the Bible as well as the historical record. In the Bible there are only two individuals named Mordecai. The first Mordecai named in the Bible is a man who returned to Jerusalem with Joshua and Zerubbabel after the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC. (Cyrus’ decree ended the 70 years Babylonian captivity). The second individual named Mordecai in the Bible is Esther’s Mordecai.

Now these are the children of the province that went up out of the captivity, of those which had been carried away, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away unto Babylon, and came again unto Jerusalem and Judah, every one unto his city; 2 Which came with Zerubbabel: Jeshua, Nehemiah, Seraiah, Reelaiah, Mordecai, Bilshan, Mispar, Bigvai, Rehum, Baanah. (Ezra 2:1-2)

Now in Shushan the palace there was a certain Jew, whose name was Mordecai, the son of Jair, the son of Shimei, the son of Kish, a Benjamite; 6 Who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captivity which had been carried away with Jeconiah king of Judah, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away. {Jeconiah: also called, Jehoiachin}

7 And he brought up Hadassah, that is, Esther, his uncle’s daughter: for she had neither father nor mother, and the maid was fair and beautiful; whom Mordecai, when her father and mother were dead, took for his own daughter. (Esther 2:5-7)

In the secular historical record the name Mordecai is just as rare. According the Gerard Gertoux, out of 16,000 cuneiform records dating to the Neo-Babylonian period only two individuals named Mordecai (Marduka) are found. I quote Mr. Gertoux:

Did Mordecai and Esther leave traces in the Neo-Babylonian documents? The name “Mordecai (Mar-duk-ka)” is relatively rare; it is sometimes found during the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus32, unlike the name “Marduk”, typically Babylonian (always written dAMAR.UTU “calf-sun”, originally pronounced amarutuk)33, which was widely used. For example, a contract dated 16/XI/8 of Nebuchadnezzar (February 596 BCE) reads34:

Adi’ilu, son of Nabu-zer-iddina, and Ḫuliti, his wife (the divine Ḫulitum) have sold Marduka, their son, for the price agreed upon, to Šula, son of Zer-ukin. The liability to defeasor and pre-emptor, which is upon Marduka, Adi’ilu and Addaku respond for.

Among the cuneiform sources dating to the period of the Neo-Babylonian empire, of which 16,000 have been published35, there are only 2 individuals bearing the name Marduka: an entrepreneur36 who did business under Nabonidus until the year 5 of Cyrus (534 BCE), and a administrative superintendent37 who worked under Darius I from his years 17 to 32 (505-490 BCE), exactly the same period as Mordecai worked38. (Gerard Gertoux – Queen Esther Wife of Xerxes: Historical, And Archaeological Evidence, p. 13-14)

Mordecai the Babylonian

Mordecai the Babylonian

Considering the rarity of the name Mordecai in the Biblical and historical record, it seems like a rather strange coincidence that there are two Mordecai’s mentioned in the Bible. This curious fact is further compounded by the fact that Mordecai is derived from the name of a pagan idol (god), the use of such names are strictly prohibited in the Bible.

And in all things that I have said unto you be circumspect: and make no mention of the name of other gods, neither let it be heard out of thy mouth. (Exodus 23:13)

Typically in the Bible, you see exceptions to this rule when those names of idols/gods are the basis for the names of Biblical heroes renamed by their captives. For example Daniel’s companions were named Hananiah, Mishael, and Azraiah, but the Bible also identifies them by their Babylonian names of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

So here in Ezra 2 we have a man with a Babylonian name, who is listed among a group of Jewish men with only Hebrew names who are returning to Jerusalem to build the city and the temple. Why didn’t the author of Ezra use this man’s Hebrew name? In keeping with Biblical tradition, the only reason that makes any real sense is that the author of Ezra 2 used the name Mordecai because it was a person more readily known to his Jewish readers by that name than his Hebrew name. In other words, one must at least consider the possibility that this Mordecai was none other than the Mordecai of the book of Esther and the author of Ezra was drawing our attention to this fact.

Mordecai, Nehemiah, and Darius ‘the great’ Artaxerxes

It’s fascinating, don’t you think, that as we learned above there are Persian cuneiform records which date a high Persian official named Mordecai to the years 17-32 of the reign of Darius I, the very same time frame that Nehemiah served as governor of Jerusalem under Darius – who we’ve learned in this series the Bible also identifies by the Persian title “Artaxerxes”.

14 Moreover from the time that I was appointed to be their governor in the land of Judah, from the twentieth year even unto the two and thirtieth year of Artaxerxes the king, that is, twelve years, I and my brethren have not eaten the bread of the governor. (Nehemiah 5:14)

Among the cuneiform sources dating to the period of the Neo-Babylonian empire, of which 16,000 have been published35, there are only 2 individuals bearing the name Marduka: an entrepreneur36 who did business under Nabonidus until the year 5 of Cyrus (534 BCE), and a administrative superintendent37 who worked under Darius I from his years 17 to 32 (505-490 BCE), exactly the same period as Mordecai worked38. (Gerard Gertoux, Queen Esther Wife of Xerxes : Historical and Archaeological Evidence)

These fascinating historical details are wrought even more curious by the fact discussed above that a man name Mordecai was listed among a group of Jewish men who led the return to Jerusalem just a couple of decades earlier. Could they be the same man?

Ironically, it is the book of Esther and Mordecai’s lineage as given there that provides a fascinating solution to the curious use of Mordecai in the Bible and this Biblical hero’s relationship to the Mordecai mentioned in the cuneiform records of Darius I.

Mordecai and Esther were Cousins

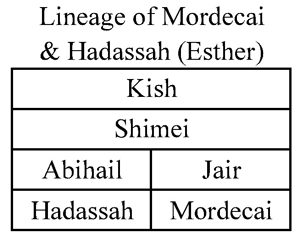

To help us determine when Mordecai lived, we return to Esther where it tells us that Esther and Mordecai were cousins. Further this passage also gives us the lineage of Mordecai as it relates to the captivity of Jehoiachin (aka Jeconiah).

Now in Shushan the palace there was a certain Jew, whose name was Mordecai, the son of Jair, the son of Shimei, the son of Kish, a Benjamite; 6 Who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captivity which had been carried away with Jeconiah king of Judah, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away. {Jeconiah: also called, Jehoiachin} 7 And he brought up Hadassah, that is, Esther, his uncle’s daughter: for she had neither father nor mother, and the maid was fair and beautiful; whom Mordecai, when her father and mother were dead, took for his own daughter. (Esther 2:5-7)

Now in Shushan the palace there was a certain Jew, whose name was Mordecai, the son of Jair, the son of Shimei, the son of Kish, a Benjamite; 6 Who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captivity which had been carried away with Jeconiah king of Judah, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away. {Jeconiah: also called, Jehoiachin} 7 And he brought up Hadassah, that is, Esther, his uncle’s daughter: for she had neither father nor mother, and the maid was fair and beautiful; whom Mordecai, when her father and mother were dead, took for his own daughter. (Esther 2:5-7)

Now when the turn of Esther, the daughter of Abihail the uncle of Mordecai, who had taken her for his daughter, was come to go in unto the king, she required nothing but what Hegai the king’s chamberlain, the keeper of the women, appointed. And Esther obtained favour in the sight of all them that looked upon her. (Esther 2:15)

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_PLUS]

In the passage above it gives the lineage of Mordecai relative to the captivity of king Jehoiachin. Now there are two ways to read Mordecai’s lineage relative to the captivity of Jehoiachin. Either Kish was taken captive with Jehoiachin or Mordecai was. Both are legitimate ways to read the passage, but thankfully we are not left to flipping a coin in order to decide who the passage had in mind.

There are two further facts that help us nail this down. First of all, we know from 2 Kings 24 that Jehoiachin’s captivity began in the 8th year of Nebuchadnezzar (594 BC). The second piece of information we have that helps us develop the chronological context of this passage is that Esther was a young maiden (narah) when she was brought before the Persian king the Bible identifies as Ahasuerus.

10 At that time the servants of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came up against Jerusalem, and the city was besieged. } 11 And Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came against the city, and his servants did besiege it. 12 And Jehoiachin the king of Judah went out to the king of Babylon, he, and his mother, and his servants, and his princes, and his officers: and the king of Babylon took him in the eighth year of his reign. (2 Kings 24:10-16)

13 And he carried out thence all the treasures of the house of YHWH, and the treasures of the king’s house, and cut in pieces all the vessels of gold which Solomon king of Israel had made in the temple of YHWH, as YHWH had said. 14 And he carried away all Jerusalem, and all the princes, and all the mighty men of valour, even ten thousand captives, and all the craftsmen and smiths: none remained, save the poorest sort of the people of the land. 15 And he carried away Jehoiachin to Babylon, and the king’s mother, and the king’s wives, and his officers, and the mighty of the land, those carried he into captivity from Jerusalem to Babylon. {officers: or, eunuchs} 16 And all the men of might, even seven thousand, and craftsmen and smiths a thousand, all that were strong and apt for war, even them the king of Babylon brought captive to Babylon. (2 Kings 24:10-16 )

2 Then said the king’s servants that ministered unto him, Let there be fair young virgins sought for the king: 3 And let the king appoint officers in all the provinces of his kingdom, that they may gather together all the fair young virgins unto Shushan the palace…. (Esther 2:2-3)

8 So it came to pass, when the king’s commandment and his decree was heard, and when many maidens were gathered together unto Shushan the palace, to the custody of Hegai, that Esther was brought also unto the king’s house, to the custody of Hegai, keeper of the women. (Esther 2:8)

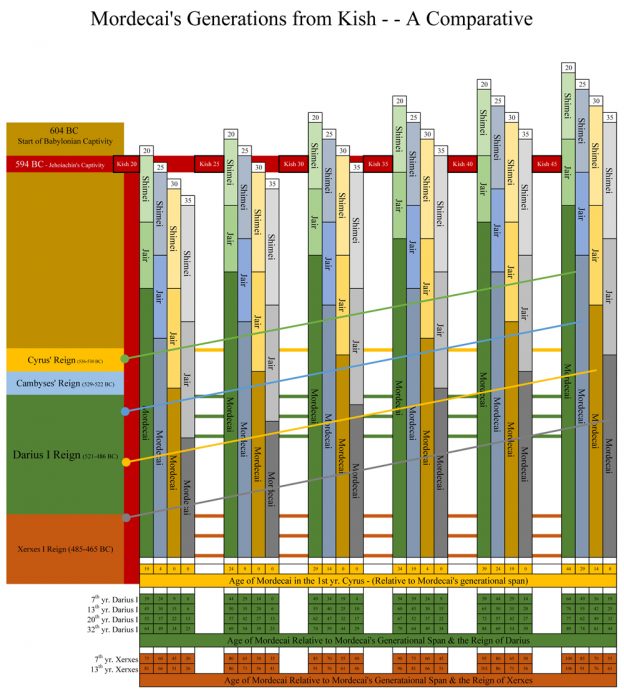

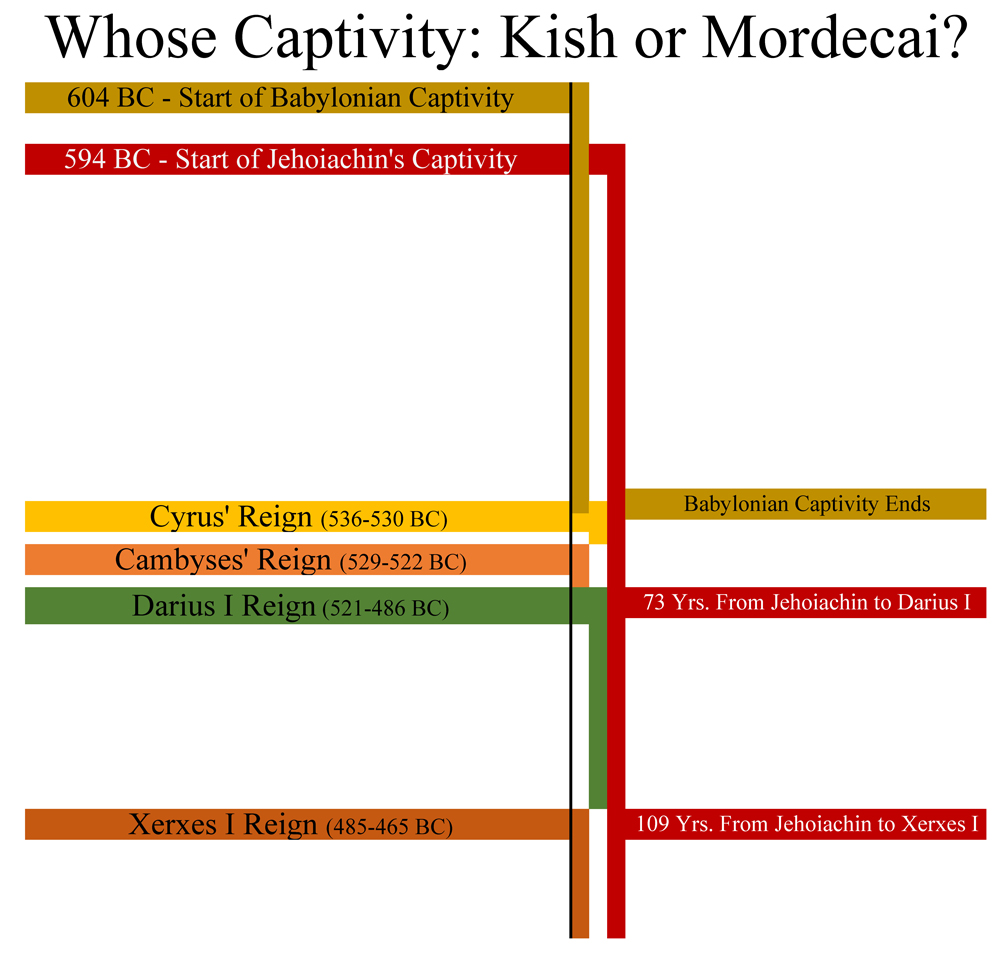

So take a look at the following chart. This chart shows the start of Jehoiachin’s captivity relative to the Persian kings Darius I and his son Xerxes I. Most Biblical scholars date the book of Esther to the reign of Xerxes and as you can see there are 109 years between the start of Jehoiachin’s captivity and start of the reign of Xerxes.

Since Esther was a young maiden at the time of her marriage to King Ahasuerus and further since Esther and Mordecai were cousins this means that even if Esther was 20-30 years Mordecai’s junior, Mordecai could not have been taken captive with Jehoiachin. This then tells us Esther 2 has Kish’s captivity in mind when it discussed it relative to the captivity of the Biblical king Jehoiachin. Even if we try to argue that Darius I might have been Esther’s king, Esther 2 could not have been referring to Mordecai’s captivity because again Esther would not have been, by any reasonable chronological criteria, a young maiden if Mordecai was taken captive with Jehoiachin. Therefore it must have been Kish’s captivity who the author of Esther had in mind and this further tells us that there were three generations between Jehoiachin’s captivity and the events described in the book of Esther.

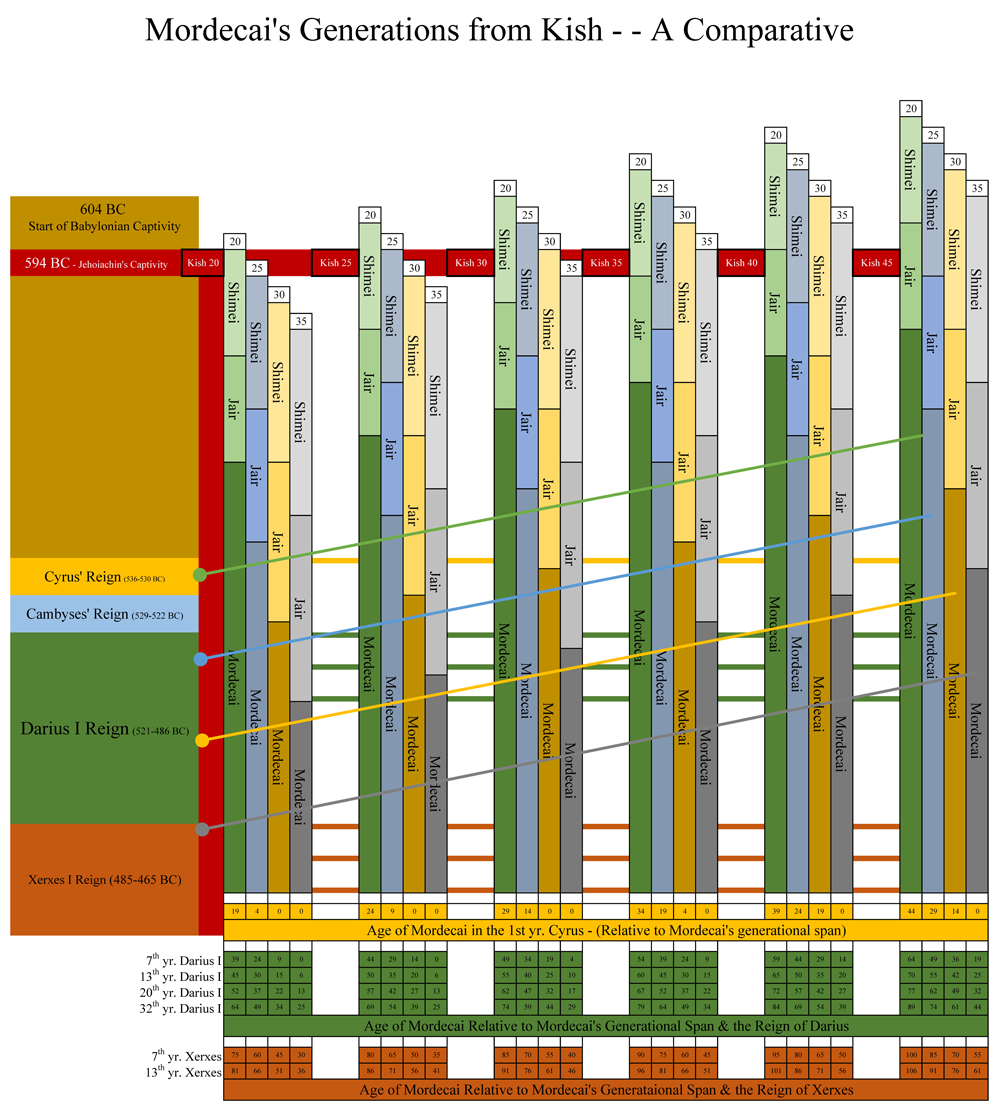

As I’ve been thinking and writing about this subject over the past couple of weeks I’ve been asking myself how I could best visually represent the chronological information related to Mordecai, Esther, and the Persian era so as to provide myself and those of you reading this article a unique way of looking at which Persian king best fits the chronological criteria for the book of Esther and the Persian record. The chart at the bottom of this page, I hope gets close to that goal.

In the chart at the bottom of this article the start of Kish’s captivity in 594 BC is the basis for all calculations. Since we don’t know Kish’s exact age when he was taken captive in 594 BC, I’ve provided several different options for Kish’s age at the start of his captivity. The range I’ve provided between 20 and 45 is based in part upon the criteria of 1 Kings 24 where it tells us that when Nebuchadnezzar took Jehoiachin captive he also took all the craftsmen and smiths and those “apt” for war. (see 1 Kings 24 reference above )

Using this information as a working basis I had to then figure out how to represent various generational spans so as to provide the best possible overview of how the different generational spans might influence the number of years between the captivity of Kish and the events described in the book of Esther.

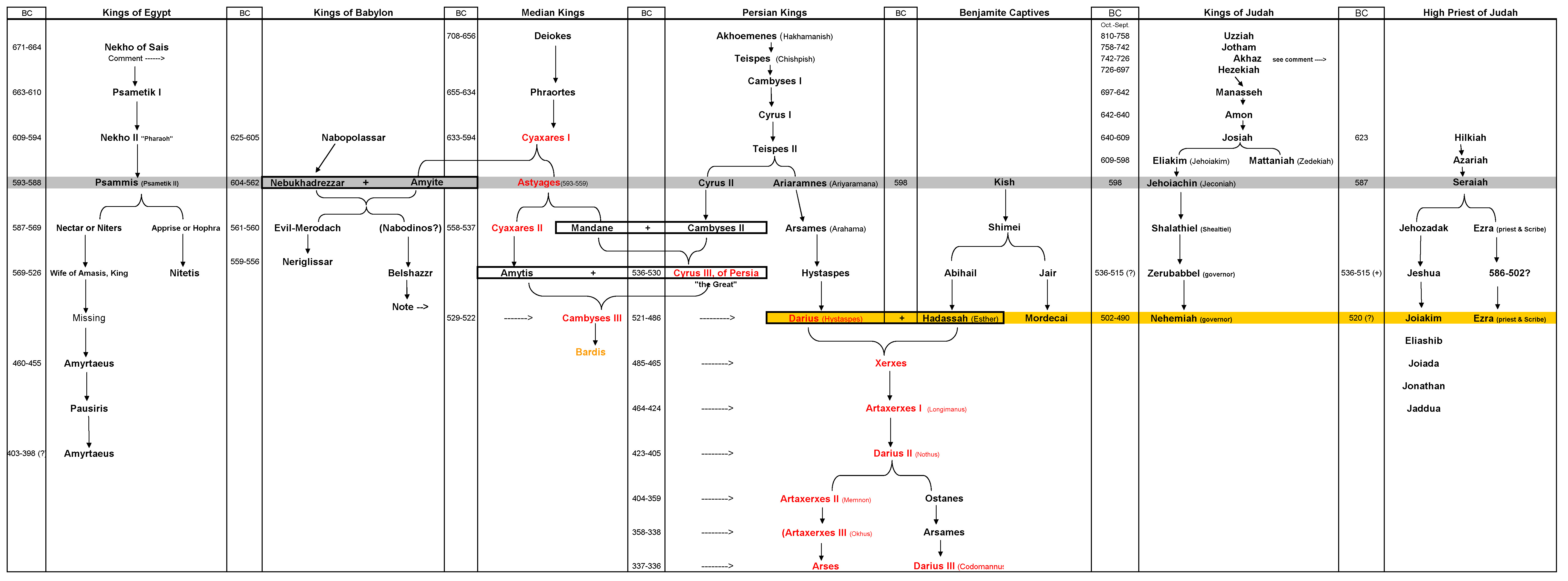

Based upon my own understanding of the demographics of that era, a 25-35 year generational span best reflects the average generational span between the people of the 2nd temple period. In the following chart a 25-35 year generational span is confirmed by the generational lists of the Egyptian, Babylonian, Median, and Persian kings as well as the lists of Judean kings and high priests. Please note that this chart is based upon a chart found in R.E. Tyrwhitt dated 1868. I’ve modified the chart for clarity and added the lineage of priests and Levites.

(please click on image to enlarge)

With this chart confirming a 25-35 year generational span between the contemporaries of that era, here are some quick reference points for the final chart below:

-

- Jehoiachin’s captivity and Kish’s various ages at the start of the captivity are represented in red.

- Each different age assumption for Kish also has its own comparative generational span from 20-45.

- The 1st year of Cyrus is marked with a horizontal bar across the chart. This date represents when the Mordecai of Ezra 2 went up to Jerusalem with Joshua and Zerubbabel in 536 BC.

- The 1st, 7th, 13th year of Darius are represented by horizontal green bars across the chart. This allows us to ascertain a range of dates for the age Mordecai and Esther during the reign of Darius I. (Esther became queen in the 7th year of a Persian “Ahasuerus”, the events of Purim occurred in the 13th.)

- The 1st, 7th, 13th, year of Xerxes are represented by horizontal rust colored bars. This allows us to ascertain a range of dates for the age of Mordecai and Esther during the reign of Xerxes. (Esther became queen in the 7th year of a Persian “Ahasuerus”, the events of Purim occurred in the 13th.)

- The diagonal bars across the chart represent the 20th year of Mordecai relative to its corresponding (color) generational span. This provides a basis to compare the age of Esther and Mordecai relative to the Persian kings. It is unlikely that Esther and Mordecai were the same age but the diagonal lines give you good reference points from which to work from. Esther could have been the same age or as many as 20-30 years Mordecai’s junior. The diagonal lines allow you a basis to work from for further comparative analysis.

- Finally, the numbers at the bottom of the chart show the age of Mordecai relative to the 1st year of Cyrus, the 7th, 13th, 20th, & 32nd year of Darius, and the 7th & 13th year of Xerxes.

(Click on chart to enlarge)

A few things are evident from the chart. If we are looking for a Persian king during whose reign all the Mordecai’s discussed in this article might have referred to the same person, that could have only occurred during the reign of Darius I. Indeed, if Darius I was Esther’s king then Mordecai could have been one of the men who returned with Joshua and Zerubbabel in 536 BC, he was likely the same official mentioned in the Persian cuneiform records, and he certainly could have been the Mordecai mentioned in the book of Esther.

If the Mordecai of Ezra 2 and the Mordecai of Persian cuneiform records are excluded from any considerations in this chart then Xerxes is still a possible candidate for Esther’s kings. That being said, if we are looking at this chart as representing a window of probability into the identity of Esther’s king then that window is several times larger during the reign of Darius I than his son Xerxes. (This window we will narrow still further in subsequent articles.) In other words, the likelihood that Mordecai lived during the reign of Darius works across a wider array of generational spans than it does during the reign of Xerxes. Excluding any other limiting factors relating to the other historical Mordecais in this chart, this window of probability regarding the reign of Darius should cause the serious student of the Biblical history to carefully consider the likelihood that “Ahasuerus” of the book of Esther is a reference to the Persian king Darius I.

Next Time

Yahweh willing, in my next article we will further narrow our search for Esther’s king by looking at who the Persian king of 127 provinces might have been. As you’ll see only one Persian king could rightly claim this title. If space permits I’ll also address Mr. Lanser’s of ABR’s objection to considering Darius I as the “Ahasuerus” of the book of Esther. I hope you’ll stay tuned as we explore this incredibly important period in Biblical history.

Maranatha!

1Gerard Gertoux, Queen Esther Wife of Xerxes : Historical and Archaeological Evidence, p. 10)

Answering Objects from the Associates for Biblical Research

For those just joining this exploration of Biblical history, this is part VI in a series in which I am attempting to answer the challenges and criticisms raised by Rich Lanser of the respected organization Associates for Biblical Research in his article The Seraiah Assumption. In his article, Mr. Lanser vigorously disputes my view of 2nd temple history as it relates to Darius ‘The Great’ as described in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. In the links below I’d encourage you to read Mr. Lanser’s article The Seraiah Assumption as well as my responses to specific points of criticism that Mr. Lanser has raised in his article. I’d also encourage you to read Mr. Lanser’s updated thoughts in an addendum to that article that he recently published in response to and email exchange we’ve had as well as his responses to some of the points I’ve made in these articles.

Articles related to this series:

The Seraiah Assumption by Rick Lanser of Associates for Biblical Research

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping up Loose Ends by Rick Lanser

My response to Rick Lanser’s – The Seraiah Assumption:

Introduction – The Associates for Biblical Research Responds to the Artaxerxes Assumption

Part I – Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4

Part II – Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem

Part III – Darius the great Persian Artaxerxes: A Contextual Look at the Book of Ezra in the Light of Persian History

Part IV – Darius and the Kingdom of Arta

Part V – Darius, Artaxerxes, & the Bible: Confirming Royal Persian Titulature

Part VI – Mordecai & the Chronological Context of Esther

Part VII – Esther, Ahasuerus, & Artaxerxes: Who was the Persian King of 127 Provinces?

Part VIII – Darius I: A Gentile King at the Crux of Jewish Messianic History

Part IX The Priests & Levites of Nehemiah 10 & 12: Exploring the Papponymy Assumption

Thank you sir, for such a deep and clear explanation. for a beginner like me, this article was really helpful in understanding the Bible better. May God flourish you with HIS Holy Spirit abundantly even more than before for you may reflect HIS light on other.

God bless

Thank you N

Do you offer a book that covers this time period with the connection shown in the above timeline?

Yes I cover some of the material in my book Daniel’s 70 Weeks: The Keystone of Bible Prophecy. I also deal with the subject extensively in the various articles here at my website.

Regards,

William